Picoballoon Background

Picoballoons are ultra-light, high-altitude balloons designed to carry small payloads to the mid to upper atmosphere. Unlike large latex weather balloons, picoballoons use small mylar or plastic balloons, and the payloads typically way under 10 grams. This allows them to float at altitudes of 40,000-50,000 ft for extended periods, potentially for years, often circumnavigating the globe multiple times.

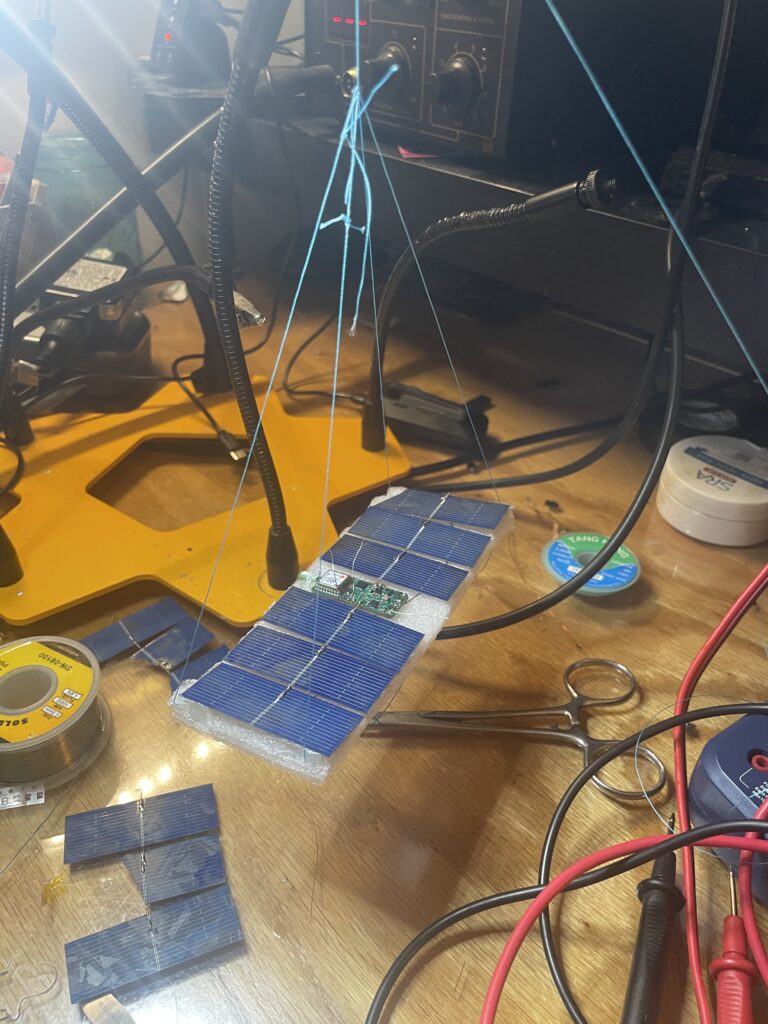

Payloads are typically powered by small solar panels and include GPS modules, low powered transmitters, microcontrollers, and sensor suites. These systems broadcast data such as positions, altitude, and temperature, allowing them to be tracked real-time as they float around the world.

Tracking Methods

One of the key difficulties with picoballoon tracking is sending the data from such a small, lower-power device back to the ground. Often, the transmitter on board is too weak for the signal to be heard when it is far away. Because of this, having networks of receivers world-wide is critical. There are two common Ham Radio networks, the Weak Signal Propagation Reporting (WSPR) network and the Automatic Packet Reporting System (APRS) network. For this project, I decided to use the WSPR network because of the simple hardware/software implementation and low-power requirements. I do plan to make an APRS-based tracker in the future for higher data rates and potential image transmission.

WSPR is a Ham Radio digital mode that was designed to be used for HF propagation condition analysis and reporting. Stations transmit WSPR messages to a network of receivers around the world which upload them to the internet so signal transmission conditions can be analyzed. WSPR messages are transmitted slowly over a period of two minutes with an immense amount of forward error correction, allowing for low-power signals to still be received. Although intended for propagation reporting purposes, these same properties of WSPR make it a great choice for picoballoon tracking, albeit with a bit of hacking to allow for more telemetry in the messages.

TeensyTrack V2 Hardware

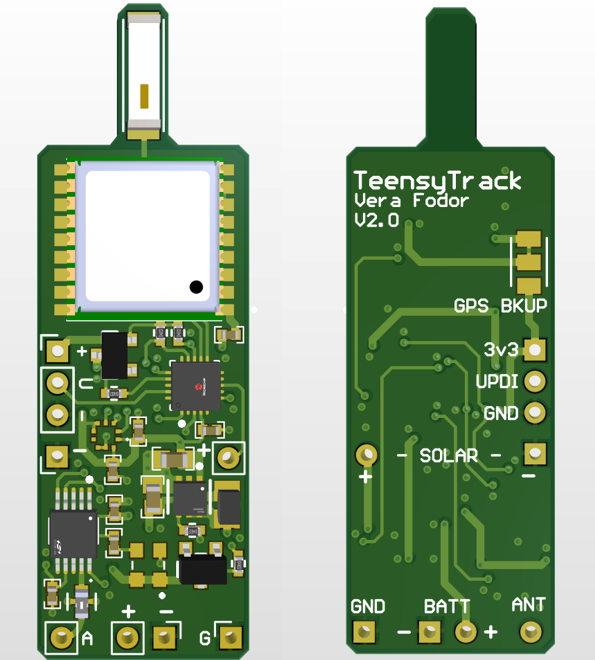

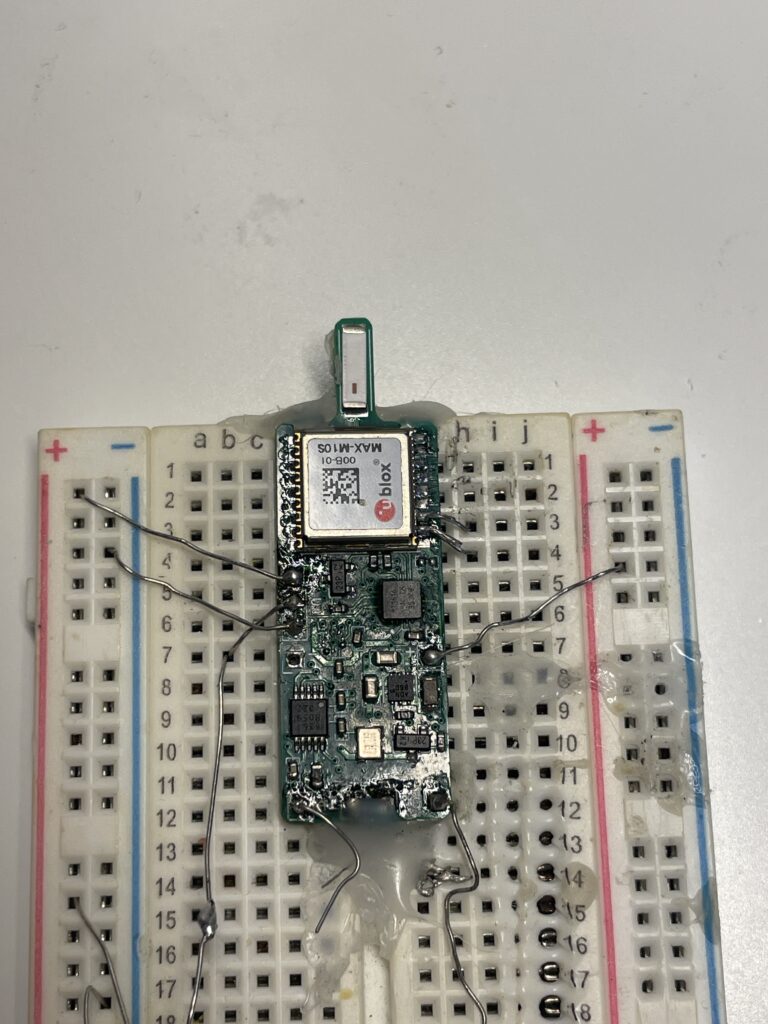

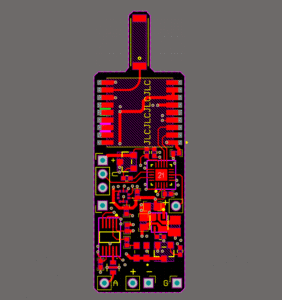

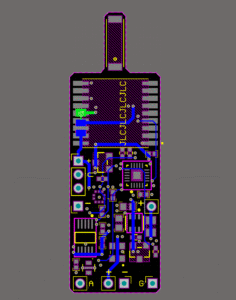

My first dedicated WSPR picoballoon tracker was based on the tinyAVR ATTiny1616 Microcontroller, UBlox Neo-10s GPS, SI5351 clock generator, and a tiny 3.3v boost converter. The boost converter takes in 1-3v from the solar panels and boosts it up to a stable 3.3v. The 3.3v output goes directly into the MCU, whereas the clock generator and GPS are powered through p-channel MOSFETs so they can be powered on/off to conserve power. Although not intended to be used as a transmitter, the clock generator can be used to transmit arbitrary frequency signals at around 10mW. The output of the clock generator is then fed into a 25 MHz low-pass filter to remove harmonics from the noisy square-wave output of the transmitter.

Software

Although there are libraries already designed to encode WSPR messages, such as Etherkit’s JTEncode, I found that they were way too large for my tiny little microcontroller. I didn’t need 90% of the features that the library had, so I wrote my own WSPR encoding library from scratch. G4JNT’s PDF on the mathematical WSPR encoding process was invaluable in the creation of my tinyWSPREncode library. The folks at Traquito have set up a WSPR telemetry encoding method where you encode additional position data, altitude, temperature, etc, as efficiently as possible using fractional bases and transmit them in a second WSPR message after the first normal one.

First Battery Powered WSPR Test

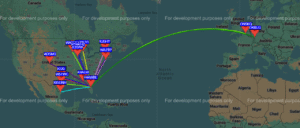

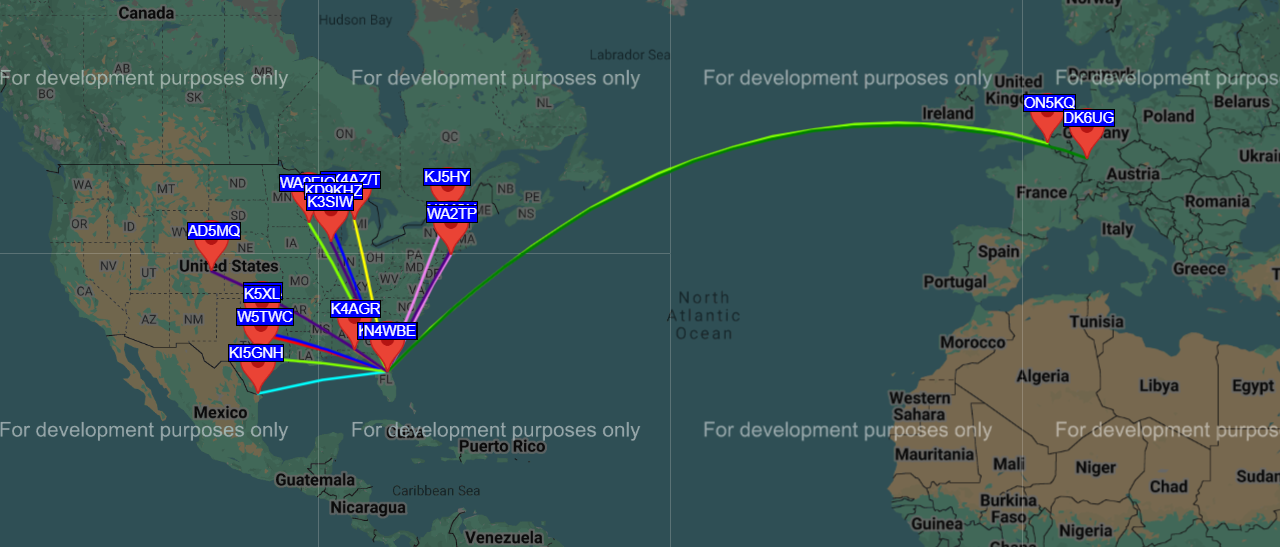

As a test, I roughly cut a 20m dipole and soldered it to the PCB along with 2 AA batteries in series to power it. I hung it from a tree, and set it to start transmitting. Low and behold, spots all over the United Stated and even in Germany with 10mW of power!!

Issues

After successfully being able to decode the transmitted WSPR messages, I went on to try to test using solar power. This is where it all went south. Under perfect lighting conditions, it worked great- powered right up, got a GPS fix, and started transmitting on its correct 2-minute interval. But whenever a cloud passed over and then away, or if the light levels slowly rose over time rather than jumping up to full brightness (such as what would happen during sunrise), the system would brown-out and brick until being fully reset. The issue was that as the voltage of the panels slowly rose, the boost converter output would also slowly rise in voltage before finally jumping up to 3.3v at a certain point. Although the MCU had a BOD voltage set of 2.9v, the GPS and transmitter IC would still experience this slow voltage rise, causing the unexpected behavior.

Pingback: Picoballoon Tracker – TeensyTrack V3 – Vera Fodor

Thanks for the insight. We sucsessfully built and launched a pico balloon from New Zealand and its currently over Argentina and going well